The back was almost totally off the 1890s "University of Michigan" parlor guitar. All of the back braces were loose (only at the ends, not in the middle,) so I took the back off to fix the braces. Under the braces, the Brazilian rosewood is scored with multiple fine lines. These line run across the grain of the rosewood, and in the same direction as the braces.

My dad, an accomplished woodworker referred to this as giving the glue joint "tooth." The original makers of the guitar must have thought that there was some benefit to this practice, or they wouldn't have taken the time and trouble to do it.

On the other hand, all the back braces were loose. Or perhaps they would have been entirely off without the tooth.

Anybody still doing this? Any ideas?

George

Views: 927

- Attachments:

Replies to This Discussion

-

wow you've discovered something very cool there cant wait to hear what everyone thinks very cool .

-

Toothing tools are sold to this day for this exact purpose. Mine came from StewMac, but I can't seem to find 'em in the catalog now. One is about 1" wide and the other about 1/2" wide. They're made of hardened steel, about 8" long, and grooved the length of the tool (about 15 cuts or so per inch). Only the sharp ends are used to 'tooth' the wood, and when the end is no longer sharp, you just grind-down the end and it's renewed. They're good for presenting an increased am't of surface for many glues to adhere-to, but (as FF said at one point) that's not the goal with hide glue.

-

My experience has been that the best joints are usually made with a very thin layer of glue. The idea being to have only as much glue as is required to hold your work together and no more. The glues I work with aren't really all that strong in and of themselves. They are by design, supposed to be very thin layers. I suppose that it would work if you grooved the back AND the gluing surface of the brace so the groove could interlock. That would increase the gluing surface but it seems to me that grooving only one side would be decreasing the gluing surface. That wouldn't be desirable to me.

Another thought is that cutting grooves across the grain of the back mean that you would be gluing your brace to short fibers rather than long fibers therefore increasing the risk of those fibers pulling free of the back.

It seems like one of those things that sounds good but may not work so well as witnessed by the fact that all your braces were loose.

Ned

-

Ned, I had a Stromberg Voisinet bridge that had to come off a guitar last year, and it was also scored like this. The guitar had been strung up since the late 20s, and the bridge showed not the 1st sign that it was about to come off.

-

Hi Kerry,

Well, maybe I'm wrong about it but I didn't actually figure it was a complete failure. It has to work, at least some of the time or it would never catch on at all. Does it work better than not grooving the wood, all other thing being equal? Were you impressed enough with the technique on the S.V that you would use now?

Ned

-

"Toothing" to improve glue adhesion is old thinking. As I understand it, we now know lots more about the electrochemical boding of adhesives, and the best joints are nice and flat, without scoring. Scoring across the grain probably weakens the joint because the fibers are cut. Here's an example of a bridge glue job where the builder of the guitar completely misunderstood the situation and overdid the scoring, allowing the top to separate like a bunch of little tiles:

Maybe you could look at this as a magnified version of what scoring might do on a micro level.

Providing "tooth" in the surfaces does have benefit for adhesives that have high cohesive strength, such as epoxy and cyanoacrylate, and it's important on nonporous surfaces for those adhesives. So, if you're supergluing a Micarta bridge to a phenolic laminate top like the Martin X series, then you really need to do some heavy surface scratching.

-

As far as I'm aware, this is a procedure that used to be thought of as a good idea, but nowadays is regarded as being contra-productive: if you think about it, it actually reduces the glue area slightly. I've never done it, I stick to the premise that the best glue joint is as smooth as possible, and is better scraped than sanded. As Ned has already said, the actual glue in the joint is really very thin, probably measured in microns. I seem to recall Frank Ford saying that it's an outdated proceedure, and mentioning that Martin used to do it, but stopped doing it some time ago, but my memory could be playing tricks on me.

Grahame

-

Howdy Ned. I would never score wood to glue a bridge on. The picture is what it looked like...

- Attachments:

-

The practice is mostly based on a mistaken understanding of the glue joint as a mechanical one--little fingers of glue reaching out and holding on to the wood like some kind of hook. In fact, that is a very minor component of the glue bond, which is overwhelmingly one of chemical adhesion.

There is one place in woodworking for scoring glue surfaces, and that is veneering. The issue there is that when gluing a wide veneer sheet, the glue may form pockets that do not get squeezed out at the edges. The scoring lines give the excess glue a place to go so that a bubble is not formed. This is not an issue for guitar making, save possibly for laminating a full width back.

Because of their cohesive strength, epoxies will work in a loose fitting wood joint. if you have a tight fitting wood joint, an epoxy joint does not gain strength by making the joint looser. This was supported by a test I recently read about; epoxies fared the best of the various glues when used with low clamping pressure, but did not do as well as they did with higher pressure. With materials that have a very low surface energy like some plastics, strength may be gained by adding surface area, as Frank says. But sanding with medium-fine sandpaper is sufficient. Coarse toothing has no advantage.

StewMac is making a mistake by offering that tool.

-

Pretty much agree and would like to add the usual fly in the ointment stuff - a lot of small shop/hobby luthiers do not have access to shear planing jointers - ordinary jointers, particularly those of the larger production shops tend to beat down and burnish/locally case-harden wood surfaces and a burnished surface is detrimental to the gluing process. Similarly, not everyone is capable of machining or planing surfaces dead flat and true.

Franklin, which makes Titebond is very clear about this in their tech application sheets.

The procedure for overcoming a burnished surface is to hand plane it (which in the case of ebony fingerboard backs is a difficult operation if you wish to keep the glue surface dead flat - which is a basic requirement for a good joint) or remachine it with a shear cut/helical head jointer (or shear cut rotary planers found in some of the large shops - sort of a big version of a safe-t-planer attachment) which will present clean, flat wood for the glue to act on.

Modern gluing procedures and practices have evolved as the finishing systems and accuracy of new systems have improved. Toothing still has a place in exposing some useful surface, 'closing-up' a bad joint and allowing extractives to be cleaned where this modern level of finishing is unavailable. Toothing did/does sterling service in the assembly of high end pianos. Sanding a surface prior to gluing is, among other things, simply a finer method of toothing.

As Howard points out, the molecular component of gluing is predominant over the mechanical bonding component in general gluing procedures we use, however, the mechanical bonding provided by sanding or toothing may well come in play more significantly if the surface being glued is burnished, not flat or poorly dimensioned - in which case toothing may be of more assistance than detriment (a detriment otherwize directly related to a small decrease in useful surface area for the molecular bonding taking place) .

Epoxy joints are used for specific purposes and have different applications and limitation that other common adhesives.

And finally, Stewmac also sells hammers, which can do a lot of damage in the wrong hands, but it is probably not a mistake to sell them.

Rusty.

-

Hammers are certainly dangerous in the wrong hands.

http://www.printculture.com/item-649.html

But the difference is that using the toothing tool as directed will not improve the joints for which it is intended.

-

They're good for presenting an increased am't of surface for many glues to adhere to, but (as FF said at one point) that's not the goal with hide glue.

Interesting, however, that they were heavily used in the era of hide glue. I think Martin may only have stopped using that technique when they went to aliphatics.

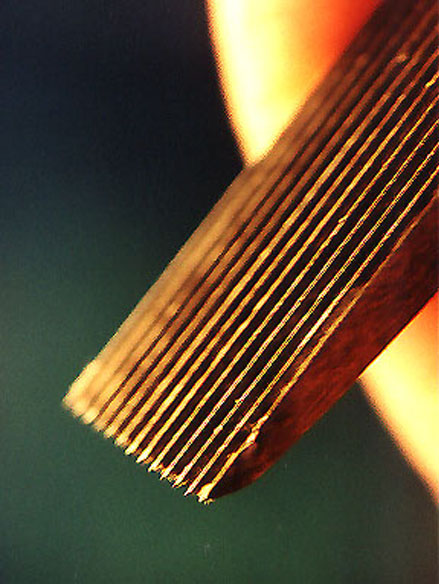

I like the technique and have used it for about 40 years, especially on bridge reglues. The tool I use started life as a narrow mezzotint rocker which I ground to a straight edge (which means it can't rock anymore on a copper plate) and that business end looks like this: That's 7/16" wide.

That's 7/16" wide.

I find it's real handy for removing brittle lacquer and other stuff, and for slightly roughing up a surface preparatory to gluing. (Not like the photo Frank showed!)

After scoring and borderline in the old lacquer, I use it like this, pulling it toward me:

The old nitro finish just shatters and pops off, but it doesn't remove wood.

I can then gently use the rocker upside down as a horizontal saw to remove all the lacquer inside and up to that scored line:

Back to surface prep for gluing, I think they probably help with penetration a bit, especially on rosewood. In any case, I don't have failures of joints, so it can't be deleterious. I think those old guys were onto something. I have a friend who did a master's in glues and adhesives at the Smithsonian and he agrees.If you're interested in what a mezzotint rocker is really supposed to do, here is a link.

© 2025 Created by Frank Ford.

Powered by

![]()